Abbasid Art: Timeless creativity and global influence

- Ali Raed

- Dec 18, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 13

The Abbasid Period is one of those moments in which some of the greatest minds in world history occupied similar spaces, building a collective legacy that would influence the following centuries. Mathematicians, scientists, astronomers, poets, and philosophers created an era of learning, laying the foundation for everyone after. Their inventions, ideas, and books remain with us today, but often seem untouchable, distant due to the pace of modern life and the speed of development, but across the country, looking at the surfaces of our ancient buildings we can see and feel this moment of the past be very much with us. I’m talking about Abbasid art.

The development of art during the Abbasid period is often just lumped together with ‘Islamic art’ and takes away the significance of its development from a crucial moment in Iraq’s history. The development of art and architectural influences the design of global design up to this day, and enhances our understanding of a period of history that is now ignored by large parts of global communities. In this piece, we will be exploring a deeper dive into the Abbasid reliefs that remain in Baghdad today and how we can connect with ancient ancestors through the walls around us.

There are several fundamental concepts that we understand from Abbasid art: geometric, arabesque, and calligraphic styles almost reflect a more formal artistic style that connects place and space to wider cosmic theory, whilst a more informal pictorial style offers glimpses into the social life of the community. The remains of this art are therefore a window into how people see the world around them and their place within it.

The geometric patterns that have become synonymous across the Islamic world with its art form truly developed in the Abbasid period as philosophers and mathematicians saw meaning in shapes. Circles as unbroken lines evoked eternity and agelessness, whilst squares represented stability, eight-pointed stars remind us of the stars and the vastness of space, whilst the concept of tessellation creates infinite repeating patterns that connect the audience to the universe, power, and creation. Walking around Mustansiriyah, under the large arched ‘iwans’ look up and see the never-ending patterns and you would be forgiven for thinking that these are representations of the stars above. Perhaps so, but they also reflect how Abbasid audiences saw the universe in their world, systematically created by God with perfection and purpose.

Arabesque patterns could also be easily repeated, connecting again to concepts of eternity and infinity whilst also celebrating the beauty of nature and creation. Foliate patterns that drew inspiration from the natural world were brought into buildings that emphasised the interconnected nature of ‘civilisation’ and the natural world. The role of the natural world in art was nothing new to ancient Mesopotamian peoples, the iconic concept of the ‘tree of life’ was born in the Mesopotamian basin, and its significance in Assyrian interpretations of the the role of monarchy in the universe connected gardens to concepts of government and stability, the Abbasid period was no different. Drawing on inspiration from the palm trees of Iraq, ‘palmettes’ form part of the never-ending patterns of interlocking botanic patterns. When these were originally crafted in the great buildings of Baghdad and Samarra, the cities would have been full of gardens unlike the streets around us today. It is fair to say we have lost that connection with nature that has long been a part of communities of the past but art offers a way to reconnect - plant motifs in prints, paintings, and even house plants all play a massive role in interior design today!

Calligraphic inscriptions often lined the mosques and madrassas of the Abbasid world, hand carved reliefs of koranic verses emphasised the importance of religion, and the importance that it played in society. The time in crafting these words is a testament to the skills of the stonemasons, creating physical beauty through the words of God. The beauty of the written word resonates personally with audiences, but is also a testament to the skills of the sculptors and artists who carved them so symmetrically.

These concepts became pillars of art, formal guidelines for craftsmen to express themselves physically and metaphysically. Yet pictorial images of Abbasid people, animals, and scenes can be found in manuscripts, on walls, painted on kitchenware, and carved into ancient walls. Look up at Bab Wastani, the last remaining gate of the medieval walls of the city, and you will see an image of dragons above the doorway - a motif not commonly associated with artistic or literary traditions of the middle-east. Its presence offers an interesting question, were dragons part of daily beliefs or was it more of an abstract icon for defence?

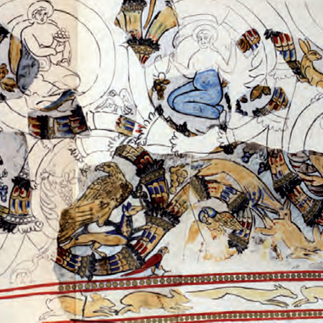

The Abbasid palaces of Samarra also give us fascinating insights into the social world of court life. The walls were lined with plaster and decorated with musicians, dancers, animals, and patterns, creating a colourful urban space that supports the written sources that talk about beautiful textiles, decoration, and furniture.

With such creative, yet spiritual developments occurring in the Abbasid period, it will be no surprise that the styles continued to be developed across the Islamic world. Some of the most famous examples can be seen through incredible architectural skills at World heritage sites such as the Taj Mahal, where ‘maqurnas’ line the gateways of the tomb of Mumtaz Mahal, the wife of Shah Jahan. Similar examples can be found across Safavid mosques and mausoleums where rulers sought to show their connection to the divine. In Iznik, near Istanbul, ceramic tiles were patterned with scrolling arabesque patterns that continued the tradition of bringing natural beauty into built spaces. But it was not just the Islamic world that was influenced by artistic innovations in Abbasid Iraq, Victorian Britain (especially the late 19th century) saw many travellers to the Middle East return home with ideas of beauty that they had seen, in turn creating a love of British made-middle eastern inspired tiles by William de Morgan, wallpaper with William Morris, and a wide variety of metalwares that emulated Arabic calligraphy and scaling arabesque patterns, this cultural appropriation can be perfectly seen in the Leighton House studio of Frederic Leighton, Baron of Leighton.

These traditions are a testament to the long-lasting global impact of the Abbasid arts that still resonate with us today. Whenever we see repeating patterns of plants, or beautifully carved Arabic inscriptions, we can take a moment and think about Iraq’s part in this grand artistic story. With this rich legacy, Creative Roots will be bringing an experiential exploration of Abbasid art through a tour that focuses on the styles that were developed before digging deeper into the impact and getting creative! Following research and insights based on our previous workshop, we will be delivering a hands-on experience where participants can engage with Iraqi artistic heritage in its local and global contexts. Sign up here and create your own Abbasid tiles and let the roots grow!

.png)

Comments